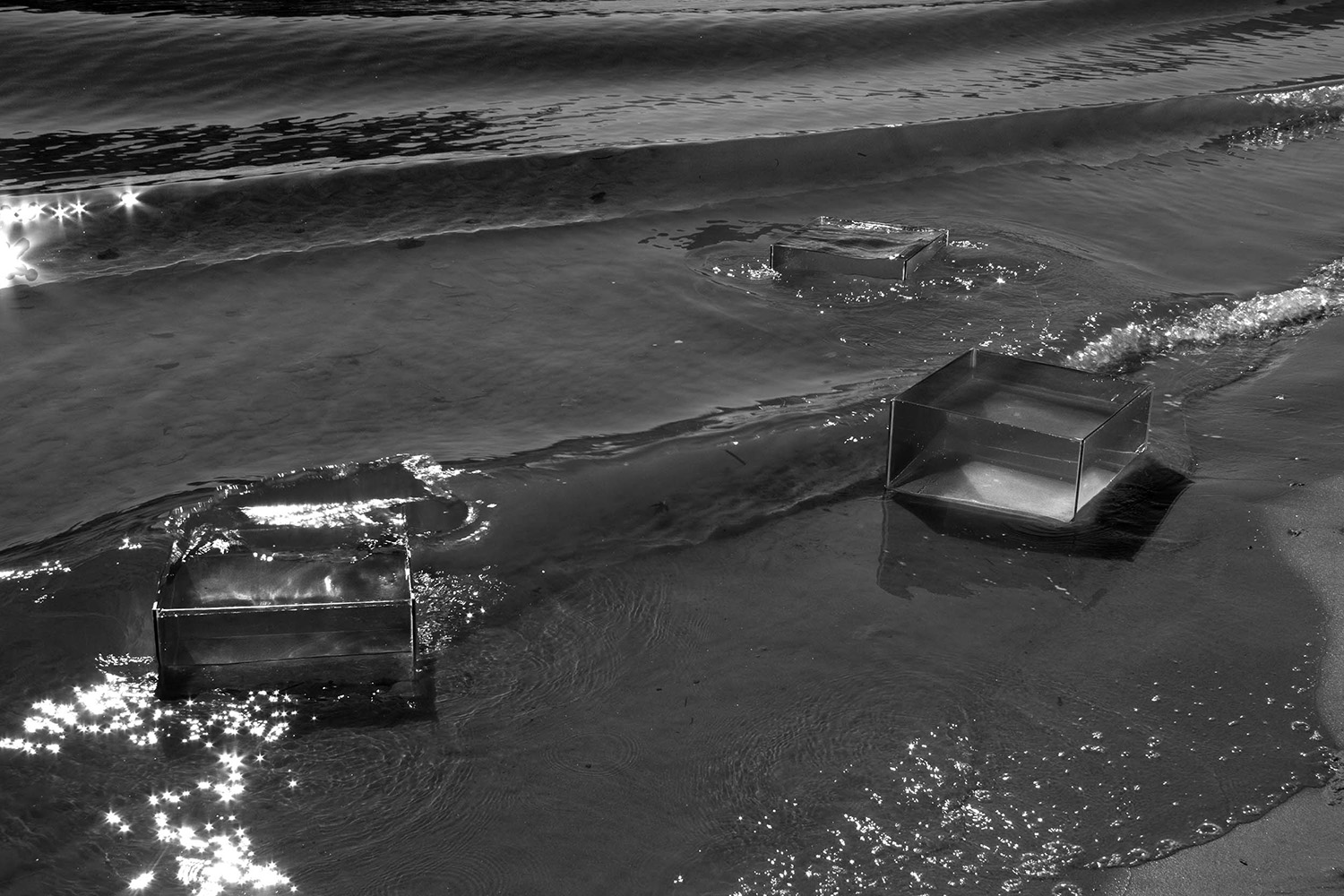

Water on Water

Framing the unframable

Connecticut River Installation x 5

2014

“Your construct is the constant - it’s always perfect. The water is the variable - it’s always changing. It’s always evolving, and it’s alive. And so by being that precise, it allows you to really appreciate the difference. And when you look at these drawings and you look at these models, it emphasizes the precision, but also emphasizes the way this has a very man-made, thoughtful quality. But the minute you start pouring the water into it, it starts to take off; it starts to have its own life. And then when you place it out in the landscape, that contrast becomes even more profound.”

Connecticut River Installation

1995

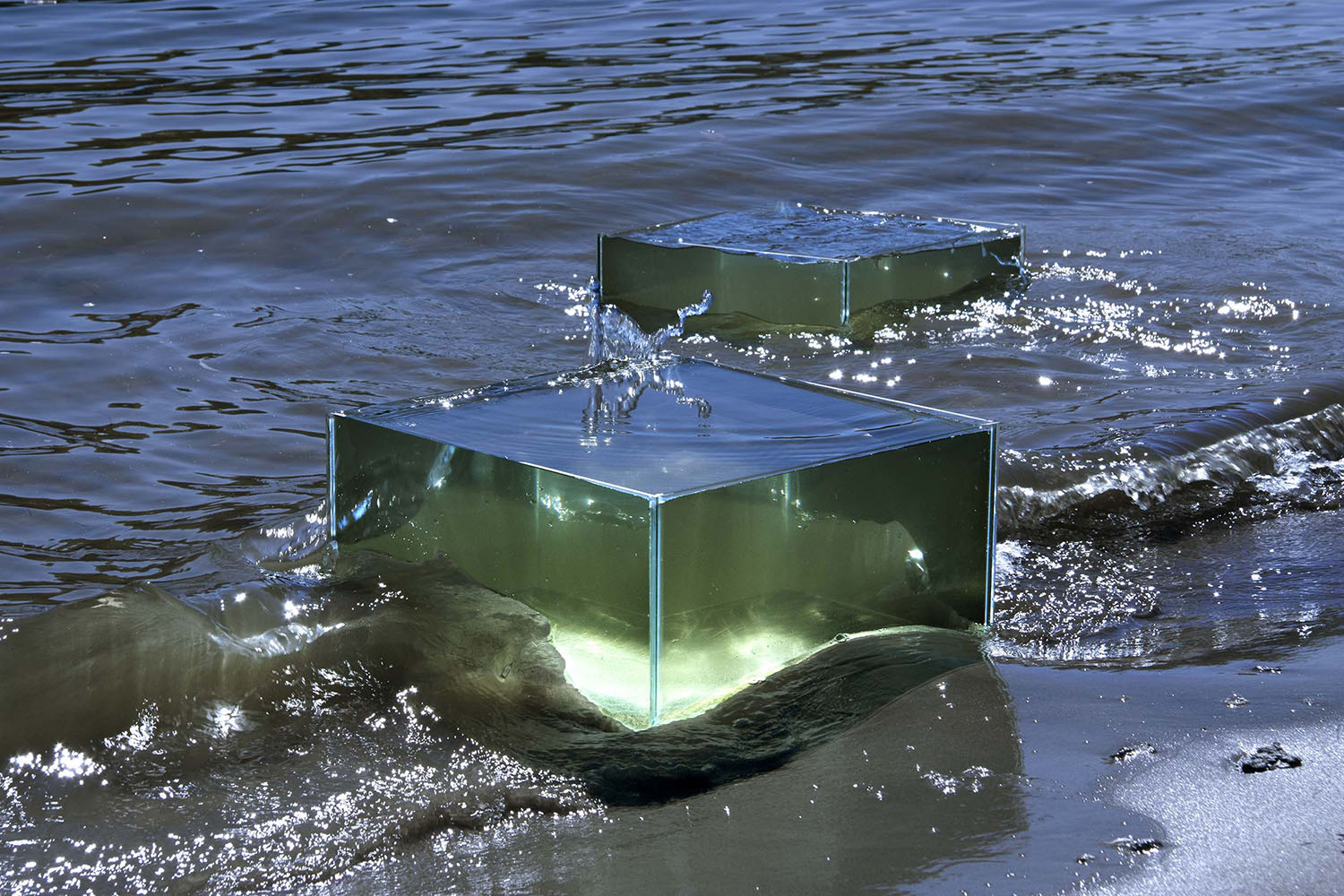

“The framing in the water, glass and light series embodies an embracing of opposites. The frame is essential. The glass construction, the framing device that holds the water, is the only way to see the water up close and in section. The contained water is isolated from a larger body of water - the river that it rests on for instance. By extracting a portion of the shapeless water, the river, and pouring it into the rigid glass structure, the frame, we are able to observe certain qualities of the water itself such as its translucency and refractive characteristics.”

Connecticut River Installation x 10

2014

"In an ongoing series of environmental installations, I have placed water-filled glass structures in various contexts: for instance on a body of water, where the structures appear to be floating on the surface. The works challenge the relationship between perception and interpretation and how we interact with place. Part ritual, part experiment, part conceptual and aesthetic art action, the installations absorb and reconfigure both the surrounding imagery and the structure of the sculpture itself, creating visual phenomena that extend beyond the parameters of water, glass and light."

Hancock Shaker Village studies

2017

The Container Frames

“From a distance, the combination of glass and water suspended on a body of water acts as a prism of sorts, illuminating the water and setting it apart from the river or pond. This compartmentalizing of something so vast and elusive intrigues me - I can observe the water, finally; not just its surface, which is usually how we see water. The surface of the water inside the tank takes on the surface of the surrounding water, and the two, the tank and the river, begin to merge. But only to a certain point - the structure of the installation pushes itself back away from the river. There is a fluidity in this push-pull and the installation always remains separate, although it seems to want to merge completely from certain vantage points and in certain light conditions. As we look at it from a structural view, and taking into account the effects of the Snell-Descartes Law of Refraction, where two dissimilar isotropic materials in close proximity change the refractive index, bending the light and causing optical anomalies, the tank becomes a constantly shifting geometrical field causing the installation to take on a varied range of optical and geometric shapes. But the changing shapes are primarily optical and don’t actually exist. It is an illusion. These interior forms that reflect the materials also reflect and mirror the visual elements of the surrounding environment: the river, the trees, the sky; or if installed inside a building: the walls, floor and ceiling, and any objects in the space. The water, glass, and light combination is collecting, re-configuring, and reflecting back all of the visual information in the environment. It is an ever-shifting cataloguing of sorts, a fluid taxonomy, by virtue of the structure and mercuriality of its system.”